Reality bites

PL cripto pode ser votada na terça-feira e movimenta entidades

December 8, 2022

As Fintechs e a revolução do sistema bancário brasileiro

January 23, 2023Brazil must do more to find foreign markets for its goods and services because domestic consumption will struggle to provide the demand the country needs to sustain its recovery, says Wagner S Moraes

In 2010, the Economist newspaper ran a cover story with Brazil as its central focus, where the good economic performance and positive outlook for the country were both exalted. Brazil was experiencing strong growth, fuelled by the policy of exemptions and consumer incentives promoted by the government of Lula da Silva, in where consumer credit lines were expanded, primary interest rates were drastically reduced in a very short period of time, and the tax burden was cut down through a diverse number of incentive policies, as well as some disastrous social ones.

Ideology supplanted the pragmatism in public management and the disaster was therefore inevitable. The foreign trade policy was insufficient to increase the country’s participation in the international commercial scene, and the focus on growth was placed on the expansion of the domestic market.

Boom turns to bust

Three years on, the Economist published a report stating that the economy had sunk. It is not hard to see why it decided to change its mind so radically. GDP growth plummeted from 4.3% per year in 2005-2010 to 2.0% per annum in 2011-2013, while investment growth fell from 9.2% to 2.3% per year.

Furthermore, in the last three years, average inflation was 6.1% per annum, and the current account deficit increased by 1.5% of GDP. Domestic interest rates rose faster as a result of the downgrade by credit rating agencies and the economy, therefore, began to convulse. There was an internal crisis unprecedented in the country’s history, which culminated in the downfall of President Dilma Rousseff. The domestic exchange rate became acutely volatile and further imbalanced the external accounts, hindering international trade.

We can define this period as ‘the flight of the chicken’ – it is fast, inconsistent, fuzzy and short-lived. Bearing in mind the same analogy with birds, the country adopted the same rhythm as the duck. It can nearly walk, almost swim and almost fly, but it cannot complete all three to perfection.

Today the country has a very weak domestic market and it is insufficient when it comes to consuming its own production. Companies have cut investments and dismissed employees, foreign trade has not advanced and the country is in an immense tradeoff. It needs to resume growth, but it does not have enough of a domestic market and it has forgotten the expansion of the foreign market. Thus, it continues to live like a duck.

As a result, Brazil is currently the world record-breaker When it comes to the prevalence of anxiety disorders, with 9.3% of the population suffering from the problem. In total, this corresponds to 18.6 million people, according to a study recently released by the World Health Organization.

With the recent change of government and possible resumption of economic pragmatism, although still very incipient, the country is once more rehearsing an economic recovery. Confidence índices are improving and presenting resumption in growth prospects, while inflation is decreasing and the Brazilian real (BRL) is appreciating against the US dollar, as interest rates start a new trajectory of decline.

Domestic demand is still quite poor and foreign trade is one of the main forces which the country needs to resume, being the main economic and most important vector, especially in a time of fiscal adjustment. It can be considered as a pillar in the resumption of growth in order to expand and create jobs.

Brazil hunts for trade partners

In international trade, while the US seems to be following a path which goes against the signing of new free trade agreements, as was made clear by President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the country from the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), Brazil, after almost 26 years of little trade integration (the last great initiative having been the creation of Mercosur in 1991), the country seems committed to pursuing new partnerships.

In the context of Mercosur, negotiation of agreements can be seen with the EU, India, Lebanon and Tunisia, as well as a deepening of negotiations with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), a bloc formed by Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

China led the ranking of countries which purchased the most products from Brazil last year, participating in 25.6% of the Brazilian export tariff, and continuing as the principal trading partner. Following China, Brazil’s largest trading partners are the EU, the US and Argentina. Such an alignment of trading partners poses a risk to the country, as China is on an economic slowdown, which is expected to worsen from the 6.7% growth registered in 2016. The EU still has serious structural problems of its own and will be consumed by Brexit, while the US is rethinking its position in world trade after the change of government, and Argentina… well, Argentina is Argentina.

With regards to the main challenges and critical success factors for Brazil to boost its participation in international trade, I can highlight the following:

• Internal balance of accounts and foreign exchange adjustment. The country must abandon its ideology and focus on management pragmatism, adjust the exchange rate so that it can have greater competitiveness in international markets, and encourage investments in the manufacturing industry. Exports are still centered on agricultural commodities and imports into industrialised consumer goods.

• The cost of logistics and insufficient channels for production outflow. Logistics costs have become higher, especially due to the insufficient, incomplete and costly transport infrastructure.

• Expansion of trade agreements. The strengthening of Brazil’s participation in Mercosur has become a straitjacket, since it has prevented bilateral and/or regional trade agreements from being negotiated, creating a sense of commercial isolation.

• Reduction of bureaucracy and expansion of lines for export promotion. It is necessary to review the processes and structure in order to provide greater exchange to the exporter, as well as to facilitate access to credit.

• Tax reform. Obsolete, complex, bureaucratic and harmful, the current Brazilian tax system is incompatible with the needs of the country, as it immobilises working capital without any compensation, hampers production and reduces competitiveness. It also makes it almost impossible to export value added goods due to the lack of time, which forces and stimulates the export of raw materials in the form of commodities, without adding value and without generating jobs in the country to do this.

These are the main actions and challenges that may generate lower costs and reduce the current rate of exchange dependency. In the current scenario, the most compatible exchange value in order for Brazil to gain market share is BRL 3.50/US$, which today it is BRL 3.09/US$. The country needs to invest more in factors of production and rely less on foreign exchange, reducing Exchange volatility and generate greater competitiveness. Eventually, it is necessary to forsake the flight of the chicken, to stop being a duck and to aim at the flight of the goose, which is organised, consistent, with high longevity, done in a team and with effective exchange of leadership.

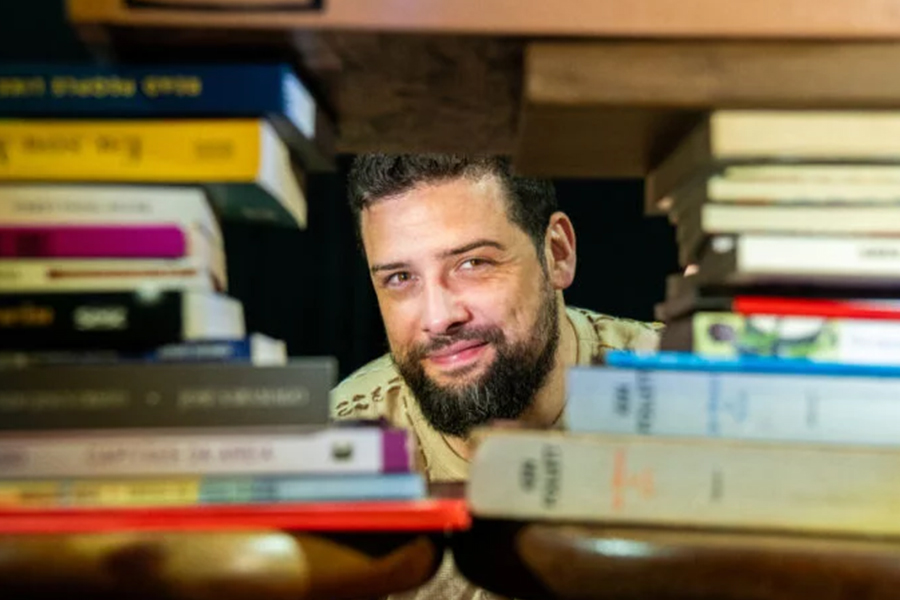

Wagner S. Moraes is executive vice president of A&S Partners